As biophilic design takes off, architects and research scientists seek a deeper understanding.

As readers of our newsletter PARTNER know, we’ve been closely tracking the boom in biophilic design and architecture for years. Considering the sheer number of schools, workplaces, offices, and shopping centers embracing the trend, one might assume that biophilic design has reached its maturation, and that its practitioners share a common language. But it’s easy to overlook the fact that the term “biophilia” (coined by psychologist Erich Fromm in the early 1970s) wasn’t popularized until 1984, when it appeared as the title of a book by biologist Edward O. Wilson, who proposed that humans possess “an urge to affiliate with other forms of life.”

At the tail end of a century of urbanization (city dwellers as a percentage of world population jumped from 15% in 1900 to more than 50% by 2007), the notion struck a chord. By the late 80’s and early 90’s an increasing number of buildings featuring green terraces, pedestrian bridges, and natural materials began cropping up across northern Europe and Scandinavia.

Decades on, however, some fundamental questions persist. How can we define biophilic design? How do we gauge its efficacy? In what ways does it enable the goals of sustainable architecture? Perhaps as a sign that it has hit the Big Time, some are calling for a more rigorous study of biophilic design and architecture, more befitting a philosophy which in short order has permeated most every aspect of public life.

In the January issue of Psychology Today, Hal Herzog reported on a recent paper by researchers at Duke University, which proposes that biophilia may not be a universal constant as first proposed by Wilson. Rather, the authors propose that biophilia is a psychological trait which should vary from one individual to the next. They further argue that the intensity of this “Biophilic Reactivity” is likely distributed on a bell curve, in which most of us fall somewhere in the middle.

The offices of SelgasCano Architecture, in Madrid

Elsewhere, a paper by faculty at the Eindhoven University of Technology makes a clarion call for a set of broadly accepted definitional terms that would encourage deeper research. “The concept of biophilic design provides many inspirations for architectural design,” write co-authors Weijie Zhong, Torsten Schröder, and Juliette Bekkering. “But architectural language is rarely used to interpret biophilic buildings.”

Central to correcting this problem, they suggest, is the scrutiny of some foundational assumptions— not least the generally accepted hypothesis which biophilic design is intended to redress: that of humankind’s “separation” from what we call nature in the first place. The authors call for a closer consideration of the notion in a broader historical context—from classical antiquity’s Hanging Garden of Babylon to the biomorphic forms of Antoni Gaudí.

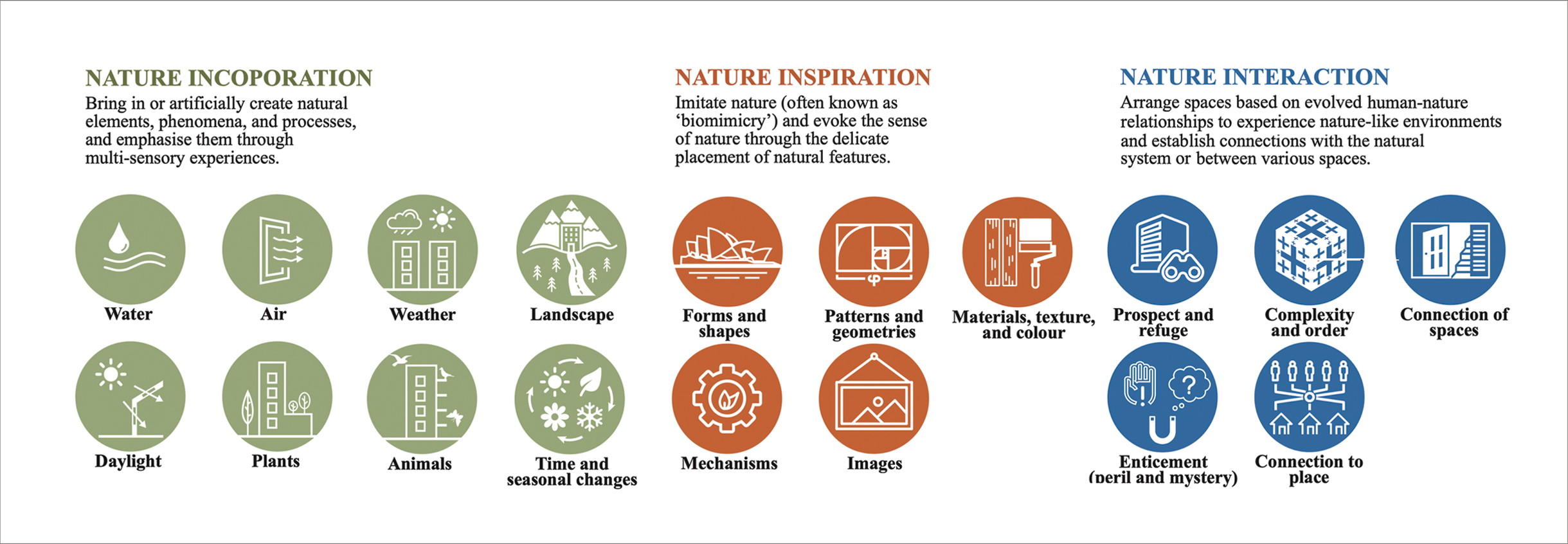

A biophilic design framework: three design approaches and primary elements

The paper highlights some issues which in biophilic design’s nascency are sometimes given short shrift or overlooked altogether—from simplified and often ambiguous notions of physical and mental health to the “double-edged swords” (e.g. insect life, excessive humidity, structural compromise) of incorporating plants into buildings.

In their challenge to architects and designers to pursue a more comprehensive, broadly spoken language for discussing things biophilic, the authors devise a draft taxonomy for the topic, pictured above. The evident necessity for such a framework excites us yet more about the biophilic design boom, not to mention its implications for crafted timberwork.

Psychology Today: “Is Love of Nature In Our Genes?”

ScienceDirect: (paper): “Biophilic design in architecture and its contributions to health, well-being, and sustainability: A critical review”

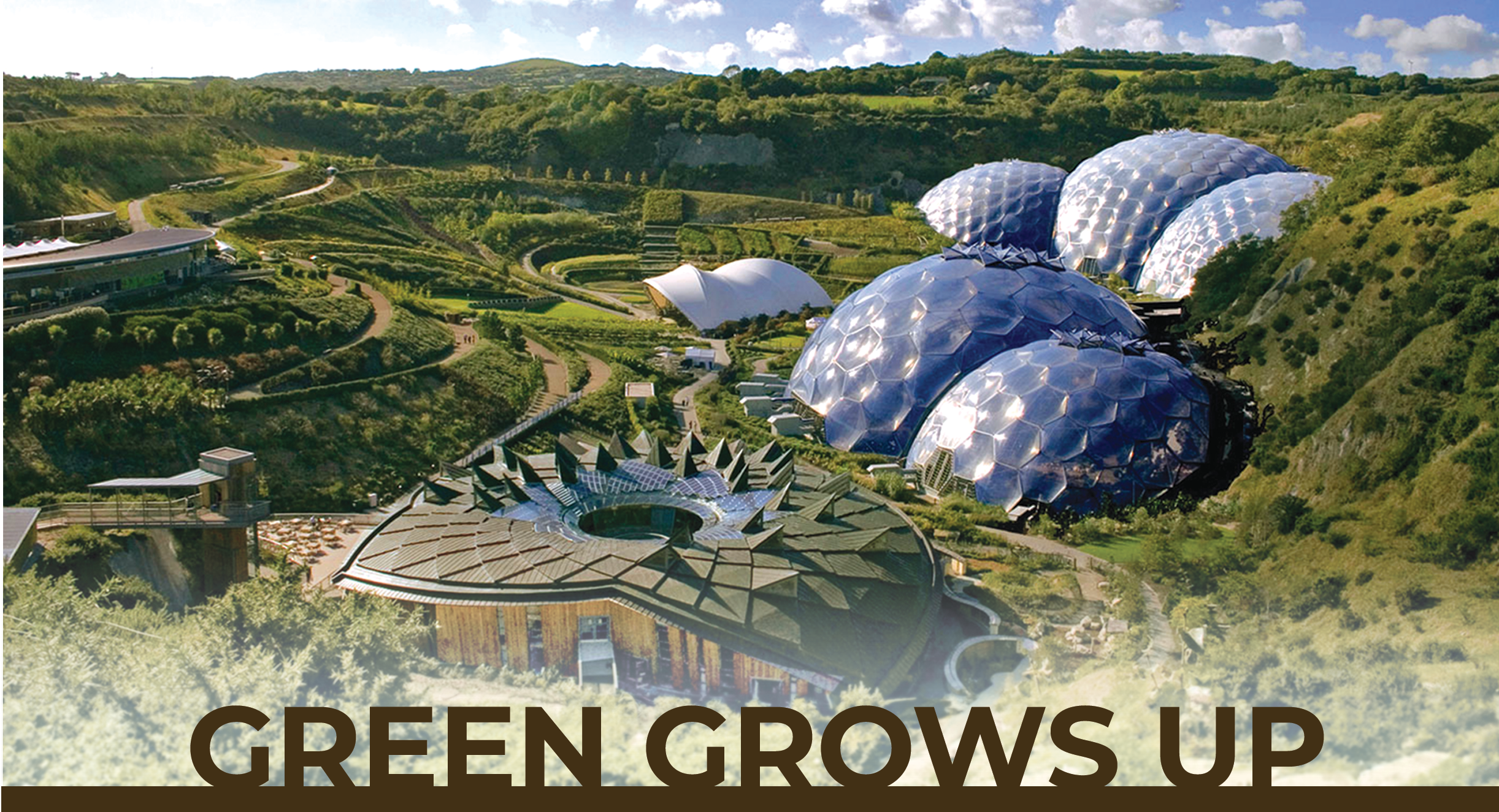

Image at top: The Eden Project, Cornwall, UK, by Grimshaw Architects